Isn’t it tragic that so many rely on their intuition for their decision-making process? Gut reactions are seen as something almost magical, acquired either by hard-earned experience or possessed by a select few genius young CEOs who deserve a top-notch pay package. Top gurus reinforce such mystical beliefs with their advice. Yet research in behavioral economics and cognitive neuroscience showing that even one training session can significantly improve the quality of one’s decision-making ability.

Baseball is Ahead of Business in Its Decision-Making Process

The “magical” mindset toward following instincts over analysis to make decisions reminds me of the era of baseball before the rise of sabermetrics, data-driven decision-making process immortalized in the book and movie Moneyball. The movie and book described the 2002 season of the Oakland Athletics baseball team, which had a very limited budget for players that year. Its general manager Billy Beane put aside the traditional method of trusting the intuitions and gut reactions of the team’s scouts. Instead, he adopted a very unorthodox approach of relying on quantitative data and statistics to choose players using his head.

Hiring a series of players undervalued by teams that used old-school evaluation methods, the Oakland Athletics won a record-breaking 20 games in a row. Other teams since that time have adopted the same decision-making process.

Coaches and managers in other sports are increasingly employing statistics when making personnel and strategy decisions. For example, in professional football, punting and field goals have become less and less popular. Why? Statistical analysis has shown that going for a first down or touchdown on fourth down makes the most sense in many short-yardage situations.

What would you pay to have similar record-breaking innovations in your business that cause record-breaking growth 20 quarters in a row? You’ll score a home run by avoiding trusting your gut and going with your head instead.

Don’t you find it shocking that business is far behind sports in adopting effective, research-based decision-making strategies? I know I do.

We have so much more tools right now in the information age to make better decisions, both in terms of the data available and in techniques that we can use to optimize our approach to making decisions. Unfortunately, prominent gurus are doubling down on the actively harmful advice of trusting your intuition in our current information age.

Why is our intuition such a bad tool for making decisions? Because we suffer from many dangerous judgment errors that result from how our brains are wired, what scholars in cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics call cognitive biases. Fortunately, recent research in these fields shows how you can use pragmatic strategies both to notice and to address these dangerous judgment errors. Such strategies apply to your business activities, to your relationships, and to all other life areas as well.

8-Step Decision-Making Process to Making the Best Decisions

So let’s set aside the bad examples of the business leaders and gurus who rely on their gut in their decisions and follow the successful strategy of using data-driven, research-based approaches. You’ll win using these strategies in business as much as you’ll win in baseball.

Effective decision making doesn’t rely either on innate talent or on hard-learned experience, contrary to the popular wisdom attributed (debatably) to Mark Twain that “good judgment is the result of experience and experience the result of bad judgment.”

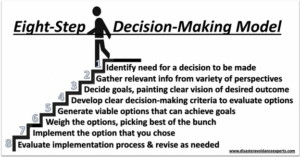

The reality is that a first-rate decision-making process is both teachable and learnable. You can boil it down easily to an eight-step model for any moderately important decision.

Hiring a new employee, choosing a new supplier, selecting a speaker for your upcoming annual conference, deciding whether to apply for a higher-level position within your company: all of these and many more represent moderately important decisions.

They won’t make or break your career or your organization. Still, getting them wrong will hurt you much more than making bad everyday decisions, while getting them right will be a clear boost to your bottom line.

Because of the importance of these decisions, wise decision makers like yourself don’t want to simply get a “good enough” outcome, which is fine for everyday choices where you’d use the “5 Questions” technique to make a quick decision. Instead, you want to invest the time and energy needed to make the best and most profitable decision, because it’s worth it to maximize your bottom line.

In such cases, use an eight-step decision-making technique, which I developed and call “Making the Best Decisions.” It takes a minimum of 30 minutes if your initially-planned course of action is indeed correct, and longer if you need to revise things. If you do need to change things around, believe me, it will be very much worth it in time, money, and grief you save yourself down the road.

This method is battle-tested: I use it extensively with my consulting and coaching for leaders in large and mid-size businesses and nonprofits. I wrote it up so that others who can’t afford my services may still benefit from my expertise.

You can elaborate on this technique for the most important or really complex decisions with a more thorough approach to weighing your options. I also suggest you use a separate technique for avoiding failure and maximizing success in implementing your decision and an additional method to address threats and seize opportunities in your long-term strategic planning. Last, but far from least, you – and those you care about – will gain a great deal of benefit from the fundamentally important mental skills of quickly and effectively overcoming cognitive biases to avoid decision disasters.

Now, on to the model itself.

First, you need to identify the need to launch a decision-making process

Such recognition bears particular weight when there’s no explicit crisis that cries out for a decision to be made or when your natural intuitions make it uncomfortable to acknowledge the need for a tough decision. The best decision makers take initiative to recognize the need for decisions before they become an emergency and don’t let gut reactions cloud their decision-making capacity.

Second, gather relevant information from a wide variety of informed perspectives on the issue at hand

Value especially those opinions with which you disagree. Contradicting perspectives empower you to distance yourself from the comfortable reliance on your gut instincts and help you recognize any potential bias blind spots.

Third, with this data you decide the goals you want to reach, painting a clear vision of the desired outcome of your decision-making process

It’s particularly important to recognize when a seemingly one-time decision is a symptom of an underlying issue with processes and practices. Make addressing these root problems part of the outcome you want to achieve.

Fourth, you develop clear decision-making process criteria to weigh the various options of how you’d like to get to your vision

If at all possible, develop these criteria before you start to consider choices. Our intuitions bias our decision-making criteria to encourage certain outcomes that fit our instincts. As a result, you get overall worse decisions if you don’t develop criteria before starting to look at options.

Fifth, you generate a number of viable options that can achieve your decision-making process goals

We frequently fall into the trap of generating insufficient options to make the best decisions, especially for solving underlying challenges. To address this, it’s very important to generate many more options that seem intuitive to us. Go for 5 attractive options as the minimum. Remember that this is a brainstorming step, so don’t judge options, even though they might seem outlandish or politically unacceptable. In my consulting and coaching experience, the optimal choice often involves elements drawn from out-of-the-box and innovative options.

Sixth, you weigh these options, picking the best of the bunch

When weighing options, beware of going with your initial preferences, and do your best to see your own preferred choice in a harsh light. Moreover, do your best to evaluate each option separately from your opinion on the person who proposed it, to minimize the impact of personalities, relationships, and internal politics on the decision itself. If you get stuck here, or if this is a particularly vital or really complex decision, use the “Avoiding Disastrous Decisions” technique to maximize your likelihood of picking the best option.

Seventh, you implement the option you chose

For implementing the decision, you need to minimize risks and maximize rewards, since your goal is to get a decision outcome that’s as good as possible. First, imagine the decision completely fails. Then, brainstorm about all the problems that led to this failure. Next, consider how you might solve these problems, and integrate the solutions into your implementation plan. Then, imagine the decision absolutely succeeded. Brainstorm all the reasons for success, consider how you can bring these reasons into life, and integrate what you learned into implementing the decisions. If you’re doing this as part of a team, ensure clear accountability and communication around the decision’s enactment.

For projects that are either complex, long-term, or major, I recommend using the “Failure-Proofing” technique to notice and address potential threats and to recognize and seize potential opportunities. That technique defends you from disasters in enacting your choices and optimizes the likelihood of you outperforming your own and others’ expectations.

Eighth, you evaluate the implementation of the decision and revise as needed

As part of your implementation plan, develop clear metrics of success that you can measure throughout the implementation process. Check in regularly to ensure the implementation is meeting or exceeding its success metrics. If it’s not, revise the implementation as needed. Sometimes, you’ll realize you need to revise the original decision as well, and that’s fine, just go back to the step that you need to revise and proceed from that step again.

More broadly, you’ll often find yourself going back and forth among these steps. Doing so is an inherent part of making a significant decision, and does not indicate a problem in your process. For example, say you’re at the option-generation stage, and you discover relevant new information. You might need to go back and revise the goals and criteria stages.

Below is a quick summary you can print out and keep on your desk.

Conclusion

Don’t be fooled by the pronouncements of top business leaders and gurus. Your gut reactions are no way to make a good decision. Even a broken clock is right twice a day, but you want to be right much more than that for the sake of your bottom line. So follow the shockingly effective example of baseball and other sports, and use data-driven, research-based approaches such as the 8-step model above to make the best decisions for yourself and your organization. To reminder yourself of the key elements of this model, you can use this decision aid.

By Dr. Gleb Tsipursky is a world-renowned thought leader in future-proofing, decision making, and cognitive bias risk management. (Consultant with IndusGuru Network Partners)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this column are that of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of IndusGuru Network Partners

#qualitydecisions #decisionmaking #effectivedecisionmaking #datadrivendecisions #researchbaseddecisions